Heading 2

Author Photo 1 300 dpi

Author Photo 1 72 dpi

Author Photo 2 72 dpi

Author Photo 2 300 dpi

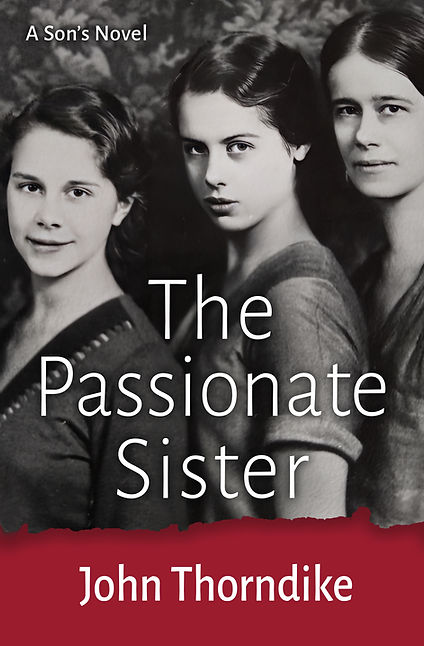

The Passionate Sister

Author: John Thorndike

Publisher Beck & Branch

Pub date Sept 15 2025

Pages: 254

ISBN paperback 978-8-9926682-1-6 Price $15.00

ISBN E-book 978-8-992682-2-3 Price $4.99

ISBN Audible 979-8-992682-3-0

Library sales IngramSpark

Author Contact jjthorndike@gmail.com

Author Website johnthorndike.com

In real life Virginia Thorndike, the author’s mother, died of a drug and alcohol overdose at the age of 57. In this novel she recovers and fights to stay clean. Her son Rob drives her home from rehab, pours her wine and gin onto the lawn and clears her house of all drugs. Her older son Jamie also comes to help, with his gay lover Miles. But when Miles is diagnosed with Lou Gehrig’s disease they return to Key West, and Ginny faces her recovery alone through a cold and quiet winter in Sag Harbor.

Soon the one who needs help will be Jamie, as Miles loses all movement and speech. Then Rob’s schizophrenic wife abandons him, leaving him to care for their one-year-old twins. Ginny moves in to help look after them, a demanding pair who sometimes elate and sometimes crush her.

Ginny hopes for a life of her own, but she hasn’t had a lover in years and can’t imagine one now. In her family she was always the passionate sister, but now her desire has vanished. Even after the devoted Lyle appears, his attention sometimes feels threatening, and she hesitates to open up to him. Slowly, she does. Passion returns, and they grow close.

Author Interview

John Thorndike is the author of four earlier novels and a pair of memoirs. The Passionate Sister is a biographical novel about his mother, Virginia. In real life she died of a drug and alcohol overdose at the age of 57. Here she recovers and stays clean with the help of her sons.

—The Passionate Sister is a novel, but clearly about your family. Where’s the line between truth and fiction?

In my previous book, The World Against Her Skin, I stayed close to my mother’s life. But even there much was invented, and in this sequel, more so. I give my mother ten more years of life, but I’m true to her nature, and her desires. I followed two rules as I wrote the book: Take anything I want from my family history, and make up anything that enriches the story.

Is this accepted? Is it fair? Forty years ago the critics would have fried me for blending fact and fiction like this. Now it’s growing common. I like what the Spanish novelist Javier Cercas says: “My aspiration was to lie anecdotally, in the particulars, in order to tell an essential truth.” The “reality fiction” novels of Michael Chabon, Karl Ove Knausgaard and J.M. Coatzee have been liberating for me, with their fluid mix of fact and invention.

The stories you tell are often intimate. What led you to write this way about your mother?

I always wanted to know about her life, but I was too reserved, too hesitant to ask her for details. She died in 1972 when I was thirty, before the emotional liberations of that decade, before I learned how to share my feelings and ask other people about theirs. I’ve long had a fantasy in which my mother gets to live for another twenty or thirty years, and we talk about everything. I think we would have.

—What about your father? Were you close to him?

There was a division in my family, perfectly obvious to me though never spoken about. My brother was on one side with my father, and I was on the other side with my mother. She and I were more inclined to what my son once called, in a high school rap, “broken hearts, emotions and feelings.” That doesn’t mean that when I was growing up my mother and I talked about such things. At best, we read about them. Often I’d find a book she left on my bedside table. Some were books for teenagers, others for adults. Often they were novels that at least hinted at passion and love and their consequences. The most powerful of these was Lawrence Durrell’s Justine, set in Alexandria before World War II, a city of “lovers, writers, diplomats, prostitutes and homosexuals.” The penciled notes my mother added to the pages of that book told me a great deal about her.

—Did she make those marks for you?

Perhaps so. But of course I didn’t ask her that, I just tracked her responses. On one page she wrote, He pays more attention to the cat than he does to me. I think she wanted me to understand why life with my father was difficult for her. And less than a year after I read that, she left him. I have great respect for my dad. It was hard for him to open up, but he was never repressive. I think he did the best he could. He once gave my mother a copy of Lady Chatterley’s Lover, because it had just been published in the U.S. and she wanted to read it. Then, how disappointed she was to discover that it was an expurgated version. Star-crossed, the two of them.

—What about those scenes you’ve written about your mother that are not just intimate, but sexual. Do you ever feel awkward about those?

I think I’m supposed to feel embarrassed about writing such stories, but I don’t. Maybe it’s because they all stem from the few comments my mother made about her affair that ended the marriage. I guess it does sound scandalous, writing about her and another man. What can I say? I want to know everything about her.

—You’ve explained that the two sons you write about in the book are not you and your actual brother. Why not?

It’s easy to write about my parents, but it was harder with my brother, as long as he was alive. He read drafts of both books, and when he felt awkward about anything, I deleted or changed it. Certainly there are traits of both of us mixed up in Jamie and Rob, the two sons in the book. Neither of us is gay, but Jamie, the gay older brother, resembles a childhood friend we both knew. In life I’m the older brother, but in the book I’m more like Rob, the younger of the two—though Rob is a truer hippie than I ever was. Unlike Rob, I was never part of a six-marriage.

—You’ve written a couple of memoirs, but your two recent books are novels. “A Son’s Novel,” it says on the covers. Your focus seems to be your family, your past, your history.

Absolutely. I am that bird that flies backward through life, trying to understand all that has come before. What’s going to come next rarely stirs me up. My son loves science fiction and future dystopias, but I wallow instead in family history. My impulse is to expose everything we were so devoted to keeping hidden, and in a novel I get to make a story of it.